Pulmonary Embolism

Incidence

Annual incidence rates for PE range from 39–115 per 100 000 population.

Pathophysiology

Venous thrombosis (DVT and PE) requires activation of the coagulation system to develop. Activation may occur without an identifiable cause (idiopathic) or due to a recognized risk factor.

Thrombosis susceptibility is individual: in some, a clot may develop caused by only a weak risk factor, while others require stronger or multiple concurrent factors. Generally, coagulation tendency increases with age.

Slowed blood flow near venous valves creates favorable conditions for coagulation activation.

PE most commonly develops when a DVT embolizes but can also occur independently.

A formed venous thrombosis may extend or resolve spontaneously. Progression of distal DVT to proximal DVT or of isolated subsegmental PE to more extensive pulmonary artery involvement is rare (<5–10% of cases).

Approximately 25–40% of venous thromboses are idiopathic, and about 30% are diagnosed in cancer patients.

Risk Factors and Etiology

There are many thromboembolic risk factors of varying degree.

Risk factors for DVT and PE may be permanent or temporary. Their classification affects treatment duration and recurrence risk assessment.

The need for etiological test/imaging after confirmed PE should be assessed individually. Routine imaging or unselective cancer screening is not recommended.

Thrombophilia testing is a special test for detecting abnormal clotting tendency.

Might be considered when idiopathic venous thrombosis or thrombosis without significant risk factors occurs at a young age (<50 years), especially if there is a clear family history.

Testing is not indicated if a significant thrombosis risk factor (permanent or temporary) is already known or if lifelong anticoagulation has already been decided on.

Testing during anticoagulation is not recommended, as acute thrombosis and anticoagulation affect coagulation tests. Genetic testing can be performed regardless of anticoagulation.

Confirmed thrombophilia may influence the duration and choice of anticoagulation, though most often other factors (idiopathic nature, risk factor severity, clot location and extent, recurrence, and bleeding risk) are more decisive.

Heterozygous Factor V Leiden and factor II prothrombin gene mutations are common in thrombophilia testing (2–5% of the population) and rarely lead to permanent anticoagulation after a first clot.

Protein C, Protein S, or antithrombin deficiency, homozygous Factor V Leiden or prothrombin mutation, or combined heterozygous defects usually warrant permanent anticoagulation.

Persistent positive antiphospholipid antibody findings (in 2 tests ≥12 weeks apart) indicate acquired thrombophilia; associated thrombotic risk and treatment duration should be assessed individually.

Diagnostic Strategy for PE

PE presentation ranges from asymptomatic to life-threatening circulatory or oxygenation impairment, or sudden death.

Diagnosis is imaging-based: CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) or ventilation–perfusion scan.

If clinical pretest probability is low or moderate → measure D-dimer.

If pretest probability is high → proceed directly to imaging (D-dimer not measured).

D-dimer can also be used in pregnancy for exclusion even though pregnancy causes elevated D-dimer levels. Use a pregnancy‑adapted YEARS approach to combine clinical criteria with D‑dimer and targeted imaging.

Symptoms and signs of PE

Possible symptoms include:

-

Sudden or progressive dyspnea, tachypnea

-

Cough, hemoptysis

-

Chest pain

-

Syncope

-

Fever (often 37–38°C), mildly elevated inflammatory markers

-

Reduced exercise tolerance

-

Hypocapnia (due to hyperventilation) and hypoxemia

-

Sinus tachycardia

Symptoms are nonspecific, especially alone.

Normal arterial blood gases do not exclude PE.

ECG may show T-wave inversion in precordial leads, right heart strain (eg partial RBBB, S1Q3T3—rare). ECG is often normal. The most common ECG finding is sinus tachycardia.

Assessment of Clinical Pretest Probability (for DVT and PE)

Pretest probability is assessed based on history, clinical examination, and risk scoring systems. An experienced physician may also estimate probability based on the overall clinical picture and determine the risk as low or high.

Using risk scores, patients are divided into three categories: low, moderate, or high clinical probability.

-

If low or moderate probability:

-

Measure D-dimer.

-

Imaging can be avoided in most cases

-

-

If high probability:

-

Skip D-dimer measurement and proceed directly to imaging.

-

D-dimer

D-dimer concentration reflects fibrin formation and degradation, a key pathogenic process in PE.

Elevated D-dimer has a positive predictive value ~50% for PE.

Non-specific elevations occur in malignancy, inflammation, atherosclerosis, post-surgical states. Advanced age and obesity also raise levels.

In preganancy, use a pregnancy‑adapted YEARS approach to combine clinical criteria with D‑dimer and targeted imaging

Imaging

Primary method: CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA).

Alternative: Ventilation–perfusion scintigraphy (=V/Q lung scan, ventilation/perfusion scan).

Normal CTPA excludes PE.

Negative predictive value: 98.8–99.1%

CTPA also assesses right heart strain (RV/LV ratio, septal flattening).

Subsegmental PE diagnoses are more common due to improved imaging; may be false positives (~5–10% of PEs).

Imaging in pregnancy

With modern imaging technology fetal radiation doses are very low (e.g., CTPA ~0.05–0.5 mGy; low‑dose perfusion V/Q ~0.02–0.20 mGy), well below the ~50–100 mGy threshold associated with deterministic fetal effects.

Echocardiography

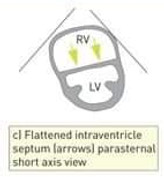

In high-risk PE, right ventricular pressure and volume increase, compressing the LV and impairing filling.

In life-threatening cases, thrombolysis can be decided based on echocardiography alone if symptoms are typical and probability is high. Echo is also valuable for differentiating causes of severe circulatory compromise.

Signs of RV strain on echo:

-

D-sign (A D-shaped left ventricle or flattened interventricular septum in PSAX view)

-

RVEDD/LVEDD ≥ 1.0 (A4C)

-

Abnormal septal motion (septal bounce)

-

RV free wall hypokinesia (McConnell’s sign)

-

TR velocity > 2.8 m/s (suggests elevated pulmonary artery pressure)

-

>3.5 m/s suggests possible chronic pulmonary hypertension (may be due to chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension).

-

McConnells sign, RV/LV ratio, D-sign on echo and CTA

Evaluation of mortality risk in patients with pulmonary embolism

In right-sided cardiac strain, proBNP/BNP levels increase, and in some patients, troponin I (TnI) or troponin T (TnT) levels also rise.

Troponin levels may be elevated even in the absence of detectable right ventricular strain.

For mortality risk assessment, tools such as the PESI or sPESI classification can be used in addition to clinical parameters alone.

A sign of high-mortality-risk pulmonary embolism is hypotension, shock, or cardiac arrest.

In low-mortality-risk pulmonary embolism there is no right ventricular strain, and troponin levels are not elevated.

American Heart Association (AHA) classification:

massive PE: sustained hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg) for >15 min secondary to acute PE or requirement of inotropes or signs of shock

Submassive PE: evidence of right ventricular (RV) dysfunction and/or evidence of myocardial necrosis (rise in cardiac troponins).

low risk PE: Patients with none of the above features

General Management of PE

Treatment pathway is determined by clinical presentation and mortality risk.

High/very high risk patients are treated with thrombolysis, or catheter/surgical intervention if thrombolysis is contraindicated or ineffective.

In practice, patients whose hemodynamics are stable but who, based on scoring systems, are classified as (very) high-risk are rarely given primary thrombolysis.

Intermediate-high risk patients are treated with LMWH usually in CCU while preparing for rescue thrombolysis if hemodynamic collapse occurs.

Intermediate-low risk patients are treated with LMWH in general ward. Patients are usually on telemetry monitoring. LMWH is followed by standard oral anticoagulation.

Initial treatment should be provided in the hospital if:

-

the patient is pregnant

-

the patient has a severe chronic illness (e.g., moderate-to-severe renal failure, heart failure, or lung disease)

Consider outpatient care if sPESI = 0 or PESI class I–II and all Hestia criteria are negative.

Subsegmental Pulmonary Embolism

In 2021 The American College of Chest Physicians suggested that in the case of an isolated subsegmental pulmonary embolism without proximal DVT, normal cardiopulmonary reserve and low recurrence risk, clinical surveillance rather than anticoagulation should be considered; if recurrence risk is high or DVT is present, anticoagulation was instructed.

The guidance is intended for patients without prior VTE, pregnancy, or cancer.

ESC states that the clinical significance of an isolated subsegmental pulmonary embolism is controversial and that if the CTPA report suggests single subsegmental PE, the possibility of a false-positive finding should be considered to prevent initiation of possibly harmful anticoagulation treatment.

Systemic Thrombolysis in PE

Thrombolytic therapy increases the likelihood of survival in proportion to the increased bleeding risk clearly only in high-mortality-risk pulmonary embolism.

In high-mortality-risk pulmonary embolism, thrombolytic therapy administered during cardiac arrest may improve prognosis.

Rescue thrombolysis is recommended if hemodynamic collapse occurs during LMWH treatment.

Thrombolysis should be avoided if symptoms have persisted for >2 weeks.

Thrombolytic therapy has not been shown to reduce the risk of CTEPH compared with heparin therapy.

Alteplase regimen:

Pulmonary embolism is an approved indication for the use of alteplase.

-

100 mg standard total dose (patients <65 kg: max 1.5 mg/kg)

-

10 mg IV bolus over 1–2 min followed by 90 mg infusion over 2 hours

-

-

In extreme emergencies (e.g., cardiac arrest) faster infusion may be considered: 0.6 mg/kg over 15 min (max 50 mg).

Half-dose alteplase regimen

May be considered if bleeding risk is high. Evidence insufficient; consider only case‑by‑case.

Half dose thrombolysis using alteplase infusion:

-

10mg IV bolus over 1-2 minutes followed by 40mg IV infusion over 2 hours

In a study comparing 3768 patients receiving 50 mg versus full-dose 100 mg of alteplase for PE demonstrated that half-dose systemic thrombolysis was ineffective, with an increased frequency of treatment escalation. However there is some evidence for the use of half dose regimen.

Adverse effects of thrombolysis:

-

Bleeding (10–15%)

-

Intracranial hemorrhage (~2%)

-

Higher bleeding risk in patients >75 years.

Rescue thrombolysis

In patients already receiving intravenous heparin, stop the infusion prior to administration of alteplase. Check activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) 2 h following completion of alteplase administration and restart heparin when the APTT ratio is <2× the upper limit of normal. If aPTT is still >80 s, measurement should be repeated every 4 hours, and therapy should be resumed when it reaches <80 s.

If therapeutic LMWH had been administered prior to thrombolysis, start heparin infusion after 18h (24h) following the last dose of LMWH if once-daily dosing and 8–10 h if twice-daily dosing had been used.

Following a good clinical response to thrombolysis, IV heparin can be switched to LMWH 24 h after thrombolysis. LMWH should be administered once UFH infusion has been off for 1-2 hours.

Checking aPTT after thrombolysis is not necessary for patients who were not started on heparin infusion therapy.

Unfractionated heparin dosing:

Initation of treatment: 80 U/kg IV bolus, then 18 U/kg/h with aPTT‑guided titration (using total body weight, Maximum = 2000 units/hour)

check aPTT every 2-6 hours

Tenecteplase

Tenecteplase has been used at doses indicated for myocardial infarction, but pulmonary embolism is not an approved indication for its use.

Invasive Treatment of PE – Endovascular and Surgical Approaches

If the patient has circulatory compromise from an acute PE and thrombolysis is either ineffective or contraindicated:

-

Pulmonary artery clot can be fragmented and removed via specialized endovascular catheter.

-

Aspiration catheters can be used without thrombolytic agents, reducing contraindications.

-

Surgical embolectomy or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) can be considered for very high-risk PE, especially if thrombolysis is not an option or has failed.

-

Surgical embolectomy is performed using cardiopulmonary bypass and direct removal of the PE through a pulmonary arteriotomy.

Anticoagulation for PE

Before starting therapy:

-

Check CBC, creatinine, ALT (and thrombophilia screen in special cases).

First-line: Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). However initial inpatient therapy often begins with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH).

Warfarin is an alternative, particularly in antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH), or severe renal failure.

Major bleeding risk with DOACs: ~1.1% in the first year.

Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin (LMWH)

Preferred for:

-

Hospitalized PE patients

-

High bleeding risk

-

High risk of thrombosis

-

Pregnancy

-

Recurrent VTE during adequate anticoagulation

-

(Cancer patients)

-

(Antiphospholipid syndrome)

Anti-FXa monitoring is necessary only in special situations (severe liver/renal failure, extreme weight, bleeding complications).

In severe renal impairment: consider tinzaparin for initial phase and warfarin for maintenance.

Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs)

Apixaban and rivaroxaban can be started without heparin, facilitating outpatient care. Dabigatran/edoxaban require ≥5 days LMWH first.

Initial and maintenance regimens:

-

Apixaban: 10 mg BID × 7 days → 5 mg BID

-

Dabigatran: LMWH ≥5 days → 150 mg BID

-

Edoxaban: LMWH ≥5 days → 60 mg QD

-

Rivaroxaban: 15 mg BID × 21 days → 20 mg QD

If indefinite anticoagulation after 6 months is chosen:

-

Apixaban 2.5 mg BID or rivaroxaban 10 mg QD is considered (not in patients with cancer or very high recurrence risk).

Warfarin

Prior to warfarin monotherapy LMWH should be used for at least 5 days.

Initial dose: 5 mg QD × 3 days, provided that INR is normal (3 mg for elderly or heart/liver failure).

INR check 3-5 days after initiation.

Adjust dose to INR 2.0–3.0.

Assessment of the risk of thrombosis recurrence and duration of anticoagulation therapy

The duration of anticoagulation therapy is influenced by:

-

previous thrombotic events

-

thrombotic risk

-

bleeding risk

-

severity of the thrombotic event

Initial phase: anticoagulation for at least 3 months for all patients.

-

Temporary major risk factor → stop at 3 months if risk factor resolved. Recurrence risk after a temporary major risk factor is <3% per year. The risk of thrombosis recurrence is the same at 3 months and 24 months after treatment, provided that there have been no changes in thrombotic risk factors during the course of therapy. If DVT or PE recurs a long time after the first thrombotic event, again triggered by a temporary major thrombotic risk factor, and there are no identifiable reasons supporting permanent therapy, a duration of 3 months of anticoagulation should be sufficient again in such cases.

Long-term therapy:

Long-term therapy beyond the initial 3 months should be considered for patients with:

-

idiopathic thrombosis

-

first DVT or PE caused by a temporary, non-major thrombotic risk factor

-

recurrent DVT or PE (unless both events were caused by a temporary major thrombotic risk factor and the interval between events was long)

-

a permanent major thrombotic risk factor

-

life-threatening pulmonary embolism

The decision to initiate long-term anticoagulation therapy after a first thrombotic event is not significantly influenced by the presence of heterozygous permanent thrombophilia, as heterozygous thrombophilia (e.g., factor V Leiden or prothrombin mutation) does not increase the risk of recurrent venous thrombosis to a meaningful extent compared with patients without inherited thrombophilia.

Long-term anticoagulation prevents recurrence but increases bleeding risk. Review annually to weigh benefits vs. harms.

Idiopathic VTE has ~40% 10-year recurrence risk, highest in first years.

The risk of recurrence is independent of whether the first episode of venous thromboembolism was DVT or PE. The clinical presentation of recurrence is often the same as that of the initial event; therefore, PE is more likely to recur as PE.

The annual risk of a fatal recurrent venous thromboembolism is approximately 0.2–0.4%. After a high-mortality-risk PE, the risk of fatal recurrence may be higher than after a low-mortality-risk PE.

No prospective randomized trials have been conducted on the effect of long-term anticoagulation therapy on mortality.

Bleeding risk associated with anticoagulation therapy

The risk of bleeding is highest during the first month after starting anticoagulation therapy and decreases thereafter.

Cancer-Associated PE

About 5% of patients with idiopathic PE are diagnosed with cancer within a year. If idiopathic thrombosis recurs, the proportion is approximately 15%.

Routine extensive cancer screening is not cost-effective and is not recommended. Screening should be guided by history and examination. CT scans are poor at detecting early-stage cancers.

Recommended cancer screening after idiopathic PE:

-

Men: clinical exam, history, CBC, electrolytes, creatinine, liver enzymes, PSA, chest X-ray (or CTPA), consider fecal blood test (FIT)

-

Women: clinical exam, history, CBC, electrolytes, creatinine, liver enzymes, chest X-ray (or CTPA), gynecologic exam (+ Pap smear), mammography (± breast ultrasound), consider fecal blood test (FIT)

In patients with pulmonary embolism, routine abdominal imaging (CT) provides no additional benefit compared to the limited cancer screening mentioned above.

In cancer patients, symptomatic or incidentally detected DVT or PE is treated with LMWH or oral DOACs.

Prefer LMWH over DOACs in:

-

High bleeding risk

-

Unresected gastrointestinal/genitourinary cancers

-

Recent major bleeding or surgery (<7 days)

-

Platelets <100 × 10⁹/L (if 25–50 × 10⁹/L, consider half-dose LMWH)

-

Severe renal impairment (eGFR <30)

-

GI comorbidity with high bleeding risk

-

Significant hepatic impairment

-

Intracranial tumor or metastasis

-

Acute leukemia

-

Cancer therapy that causes cytopenias

Follow-Up

All PE patients: follow-up visit at 3–6 months if stopping anticoagulation.

-

Assess recurrence and bleeding risk

-

Evaluate for post-PE syndrome or CTEPH

If decision on indefinite therapy is uncertain → consider D-dimer 1 month after stopping anticoagulation; elevated value indicates higher recurrence risk.

To assess treatment outcomes, echocardiography may be used in special situations. In some patients, residual thrombosis remains despite treatment as the thrombus becomes fibrotic and chronic; however, treatment duration should not be determined on this basis. Anticoagulation is not given specifically to treat post-PE syndrome symptoms (note difference between post-PE syndrome vs CTEPH). Instead, it is important to evaluate whether symptoms are due to a new thrombus or the sequelae of the previous one.

Follow-up options for patients with pulmonary embolism (PE):

A. If high CTEPH risk score points are identified at baseline, schedule a follow-up visit with ECG and proBNP or BNP testing.

B. If significantly elevated pulmonary artery pressure is detected at baseline (tricuspid regurgitation peak velocity > 3.5 m/s), but there are no clear findings suggesting CTEPH in the acute phase, schedule a direct follow-up echocardiography.

C. At follow-up, symptomatic patients should undergo ECG and proBNP or BNP testing.

D. If the patient is asymptomatic and the risk score points are low, no screening examinations are performed.

At follow-up, If proBNP or BNP values exceed the age- and sex-specific reference limits, or if the ECG shows signs of right heart strain, referral for echocardiography is recommended.

Long-Term Complications

Post-PE Syndrome

Occurs in up to 20% of patients.

-

Fatigue, dyspnea, reduced exercise capacity without CTEPH. Symptoms are caused by reduced exercise tolerance.

-

Risk factors: advanced age, cardiopulmonary disease, high BMI, smoking, elevated pulmonary pressures or RV dysfunction at diagnosis

-

In theory, residual thrombi in the pulmonary arteries may predispose patients to reduced exercise capacity, but imaging studies for this purpose are not recommended. The reduced performance capacity has instead been suspected to result from deconditioning.

-

Management: exercise training, reassurance.

-

post-PE syndrome (without CTEPH) alone is NOT an indication for indefinite anticoagulation

Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension (CTEPH)

Probably underdiagnosed. Develops in ~3% of acute PE survivors

May occur in patients without prior PE history

If echocardiography in a PE patient shows a tricuspid regurgitation peak velocity > 3.5 m/s, underlying CTEPH should be suspected

CTEPH is caused by organization of thrombus into fibrotic obstructive thrombus → increased pulmonary vascular resistance and pressure.

Can lead to RV failure

The risk of developing CTEPH is increased especially in patients with acute PE who have:

-

recurrent PE or a history of DVT

-

extensive embolization

-

signs of elevated pulmonary artery pressure on echocardiography

Early identification of CTEPH likely improves treatment outcomes.

The typical symptom is exertional dyspnea; other symptoms may include peripheral edema, chest discomfort, and fatigue.

The possibility of CTEPH should also be suspected in patients with newly diagnosed pulmonary hypertension or unexplained, persistent dyspnea without a history of acute PE.

Screening:

-

At 3 months post-PE:

-

CTPEH risk score, ECG, proBNP/BNP

-

-

a CTEPH exclusion algorithm based on ECG and proBNP results

Diagnosis:

First line: Echocardiography, V/Q lung perfusion scan

The diagnosis of CTEPH is confirmed after 3 months of appropriate anticoagulation if:

-

imaging studies show typical CTEPH changes (perfusion defects on lung scans; arterial stenoses, occlusions, or web-like changes on CT pulmonary angiography or pulmonary angiography)

-

right heart catheterization demonstrates elevated pulmonary artery pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance.

The optimal treatment modality or combination of modalities is determined by taking into account the patient’s comorbidities, procedural risks, as well as the severity and anatomical location of CTEPH

Treatment options for CTEPH include:

-

lifelong anticoagulation for all patients

-

surgery (pulmonary endarterectomy, i.e., surgical removal of chronic intraluminal thrombi in the pulmonary arteries)

-

balloon pulmonary angioplasty for arterial stenoses

-

pulmonary vasodilator drug therapy